Wildlife Diplomacy: Rangers’ critical roles managing Human-Wildlife Conflict

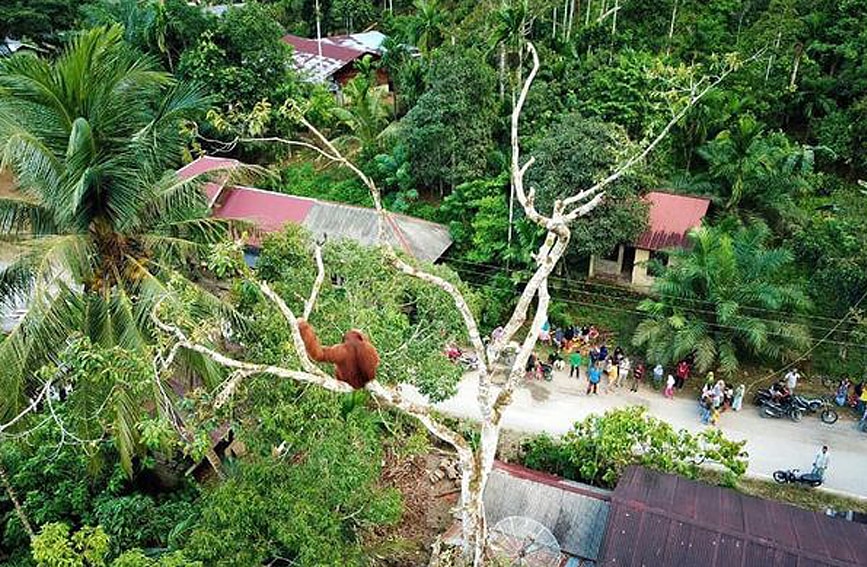

A male Orangutan venturing out of the forest near a village in Aceh Province, Indonesia. Distracted by his human onlookers, he eventually returned safely to the forest. Courtesy Leuser Conservation Forum.

Human-wildlife conflict puts rangers in peacekeeper roles, having to deter wildlife from dining-out on crops and livestock to protect them from reprisal attacks by communities.

While crop raids from herbivores are the biggest aspect of human-wildlife conflict in some African countries, predation on livestock from carnivorous animals also needs to be prevented to reduce reprisal attacks. Often retaliatory actions are misguided, for example individual lions have been hunted and killed when a leopard was the more likely culprit, and the use of poison baits has the potential to kill numerous animals in the surrounding ecosystem

Rangers’ skills and stamina are tested responding to dangerous situations night and day, protecting property, people, and wildlife.

While managing human-wildlife conflict goes a long way toward protecting the livelihoods of communities, rangers often put their own lives at risk when called on to protect communities from elephants who have left the boundaries of protected areas in search of easy pickings.

According to Jennifer Mann, Thin Green Line Foundation, villagers have been badly injured trying to protect small holdings of maize and other crops.

“Maize is just as appealing to elephants, as it is to many people,” Jennifer said. “Electric, and even chili, fences can be very effective to keep elephants away from crops.”

Protecting communities and their livelihoods subsequently protects wildlife, but deterring wildlife is not easy. Lights and sirens work well in the short term but most animals learn over time that they pose no harm. Some individual animals become repeat offenders.

“Kenyan rangers in some areas administer compensation schemes if livestock is taken by wildlife,” said Jennifer. “This gives the rangers another important role among communities living on the fringes of protected areas.”

Protecting crops and communities goes a long way to establishing trust for rangers among local people. Community members are vital sources of intelligence.

“Recognition of rangers as protectors of local communities, as well as nature, empowers them to enforce laws on grazing or wood gathering, charcoal burning or other illegal activities in protected areas,” Jennifer said.

“It’s like a United Nations peace keeping role, but in nature.”

“Our good friends at The Sumatran Ranger Project have their hands full at different times of the year, keeping tigers, orangutans and elephants away from communities.”

Camera traps and sighting pug marks on patrol provide warnings of a tiger’s movements. Using lights and alarms to warn away a tiger from the vicinity helps discourage the precious carnivores from developing the bad habit of taking a cow, instead of hunting wild prey. Work that is increasingly important for the entire ecosystem, as farmers will often place poison on a half-eaten carcass as a consequence of losing a valuable cow.

Tiger “pug mark”.

Courtesy of Sumatran Ranger Project.

A Sumatran bull Elephant.

Courtesy of Sumatran Ranger Project.

The Sumatran Ranger Project (SRP) team have also put many hours and resources into building predator-proof fences to protect livestock near national parks. However, other mitigation strategies, like managing a local gang of adolescent bull elephants, can take up even more of their time.

Three young bull elephants had teamed up to create mayhem 18 months ago. The pachyderm gang deliberately targeted forest huts and village watch towers to demonstrate their strength during nights out near local communities. Ranger teams lost a lot of sleep responding to these situations, using raucous sound and light shows to discourage the elephants from coming too close to villages.

Deterring elephants from crops outside protected areas is a very high-risk role for rangers working in Asian and African countries.

During June and July 2021, the SRP team responded to a number of incidents where orangutans have come out of the national park and into durian trees close to the forest. Durian has high economic value in Indonesia and is known as ‘the king of fruits’ throughout South-East Asia. Smallholders in forest edge communities grow this highly prized crop as it contributes significantly to growers’ income security.

Durian is nutritious and appealing to orangutans and throughout durian season (typically June to August in North Sumatra) human-orangutan conflict significantly increases as orangutans raid these crops that are planted close to the forest.

Often surrounding trees like rubber, make an easy pathway out of the forest directly into the durian tree. The ranger team have been cutting down surrounding rubber trees in particular areas, with the aim of reducing the likelihood of crop raiding.

SRP supports affected growers by responding to every incident they are made aware of, helping to drive orangutans safely back to the national park using noise deterrents and assistance from locals.

Working in the fringes between protected areas and local communities requires a lot of judgement and patience. Knowledge of wildlife behaviour and trust among community members can’t be taken for granted – evermore essential aspects of a ranger’s multifaceted role.

Ranger Serasi destroying an illegal wire snare, Leuser Ecosysetm, Northern Sumatra. Courtesy of Sumatran Ranger Project.

Thank you to our friends at The Sumatran Ranger Project for much of the information used in this article.