Where the desert meets the city

By Leigh Foster

Thin Green Line is well known for its support of rangers around the world, particularly through its provision of critical training, equipment, and its work with families of fallen rangers. One of the reasons I love being a part of the Thin Green Line team is its ‘big picture’ thinking, and – while we continue to directly support rangers with practical resources – we also look ahead and invest in areas that we know are the future of successful conservation practices.

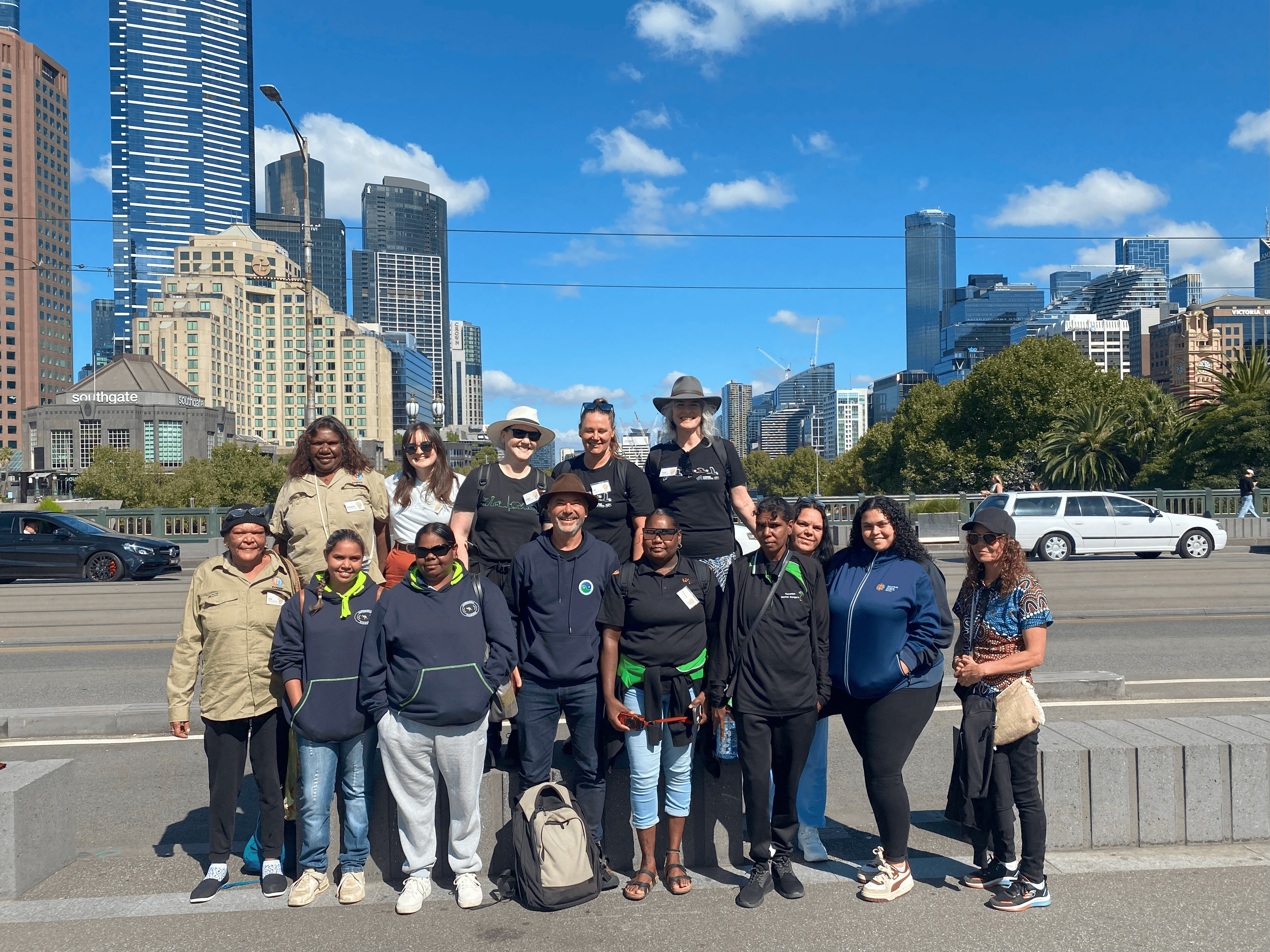

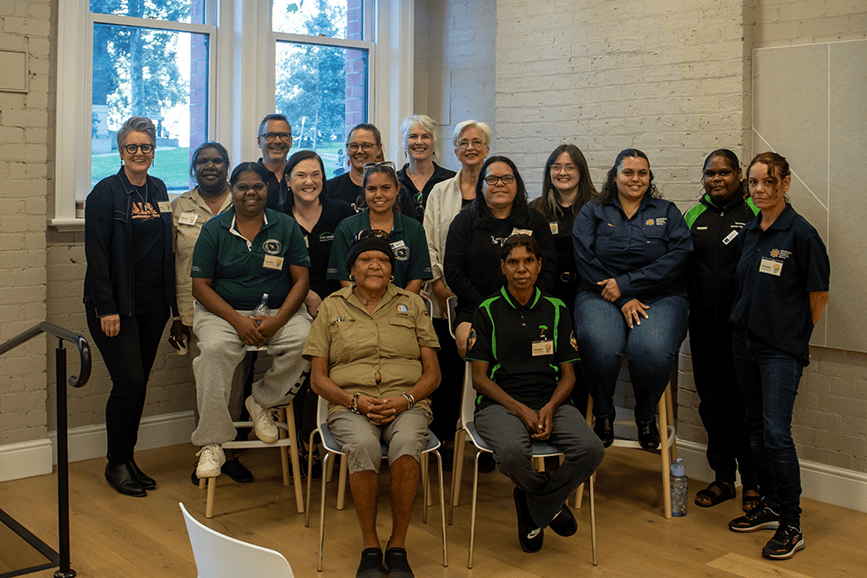

The Desert Women’s Leadership (DWL) program is one of those areas. In partnership with Indigenous Desert Alliance, Thin Green Line established the DWL in 2023 and, in March this year, we ran the program for the second time. Eight participants representing desert communities from Western Australia, Northern Territory, and South Australia, made their way to Melbourne for ten days of professional development activities. The main aims of the project are to create leadership pathways for Indigenous female rangers – to increase their confidence by way of public speaking, to empower them to engage in the mainstream world, and, perhaps most importantly, to have their voices heard by a variety of audiences in a metropolitan setting.

The Indigenous ranger sector is one of the fastest growing areas in conservation globally, but representation of women remains low. Employment opportunities in Australia’s remote desert communities are extremely limited, especially for women. The DWL program not only aims to create role models and leaders of existing female rangers, but also to encourage more women to work on Country as conservation professionals. At a time when Australia’s Indigenous peoples make up just four per cent of the total population yet manage 30 per cent of its lands and waters, it’s never been more important to enable more of our First Nations people to care for Country in an official capacity, and to be recognised properly for their intimate knowledge and traditions in conservation. We also see the unique and inclusive way in which women work on Country by welcoming communities – especially children – into the conservation space.

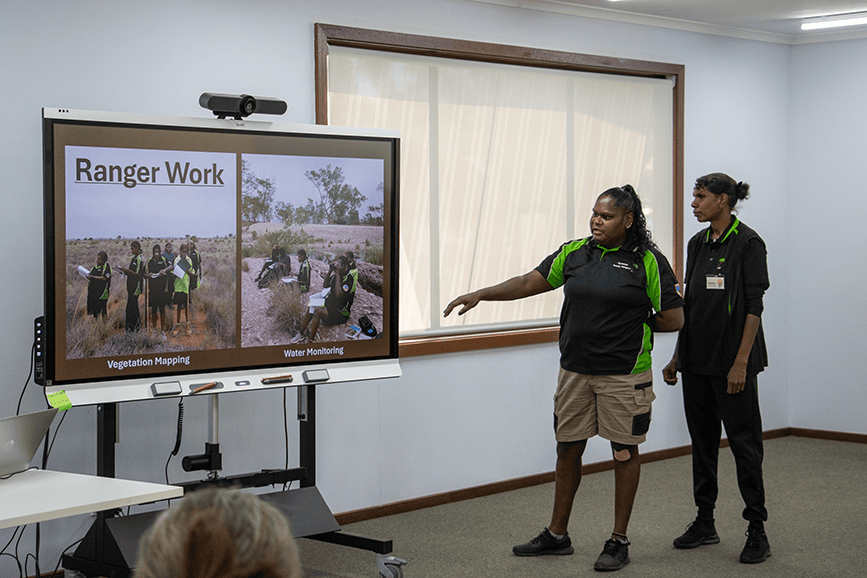

I’ve been fortunate enough to be involved in the DWL program from the start and it’s been an honour to watch these women grow and transform in the space of a week. Many of their engagements took the form of public speaking, which can be intimidating for even the most seasoned presenter! For these women, it was a daunting and, at times, an overwhelming task. However, they all rose to the occasion and, by the end of their stay in Melbourne, the group had presented their stories to a combined audience of more than 550 people including fellow rangers, school children, and corporate professionals. These varied audiences learned about the day-to-day work of a ranger in the deserts of Australia, the native wildlife that are monitored and protected, and the challenges of working in such remote environments.

The group also had the opportunity to enjoy what a big city like Melbourne has to offer, with visits to the aquarium, the BBC Experience, a game of AFL and, of course, shopping! For many it was a week of firsts – from being away from their communities, to flying, travelling on trains and trams, and experiencing a bustling city. Many of the things I take for granted were monumental to these rangers, as were the stories of colonisation and displacement of Indigenous groups in Melbourne, and Victoria more broadly. We saw, first-hand, how distressing these historical accounts can be to today’s Indigenous peoples, with many in the group expressing their feelings of sadness and grief hearing about the loss of culture and connection to Country experienced by Victoria’s First Nations peoples.

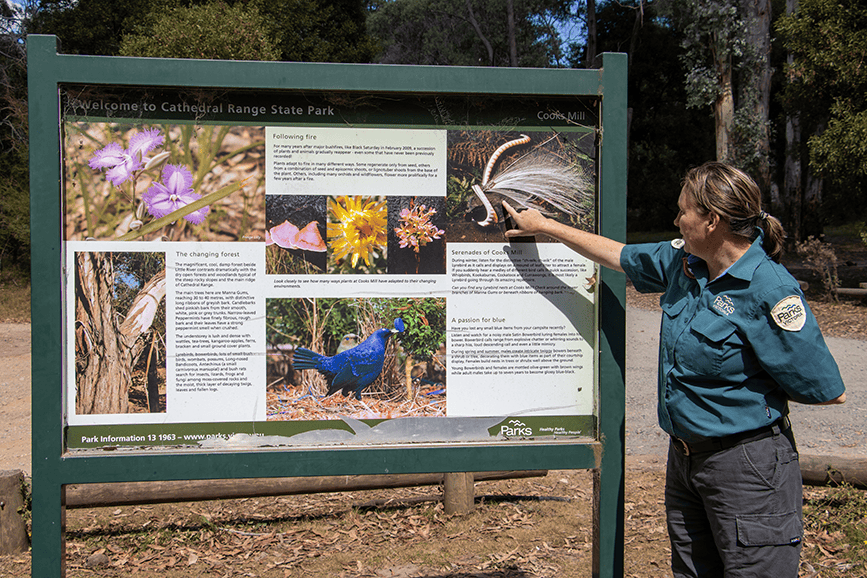

While every event that the women attended or presented at was rewarding and interesting, the stand-out for me was a visit to the Taungurung rangers of central Victoria; a small but mighty team of Indigenous rangers working in partnership with Parks Victoria to manage their traditional Country. Our journey took us to Alexandra, 130km north-east of Melbourne and through the stunning landscape of the Yarra Ranges and along the Black Spur route. Our group, having come from desert regions, had never seen Country like this before and were in awe of the tall mountain ash and the feathery tree ferns of this stunning landscape. The rangers were officially welcomed to Country by Taungurung Elder Aunty Jo Honeysett with a smoking ceremony. Being welcomed to Country was particularly important for our group, as it is for Indigenous Australians generally when visiting Country that is not their own. It’s a way of acknowledging the traditional custodians and ensuring that Country is a safe and welcoming place for visitors, offering protection as well as permission to be there.

Presenting to the Taungurung rangers was the group’s first attempt at public speaking and, despite a great deal of nerves, they performed brilliantly! A reciprocal presentation by the local rangers took place, followed by a guided visit to the nearby Cathedral Ranges National Park. Our group were taken by the sheer beauty of the place – the towering mountain range, the tall trees, and the flowing river. During their introduction, the Taungurung rangers were describing the flora and fauna of the area and admitting that, despite their time on Country, they had never seen a lyrebird; a native bird that is more often heard than seen. Our group wandered through the area, taking in the breathtaking scenery, and learning about Country from the Taungurung rangers. Personally, I love this area. Connecting with nature and being surrounded by such natural beauty is always revitalising and wonderful, but I realised that – yet again –this was something I had taken for granted and now it was being experienced in a far more profound way by our Indigenous friends. They talked of its silence that still spoke through the wind, bird calls, and running water. They paid attention to everything – from the tree canopy far above their heads, to the ground beneath their feet. They were curious about plants and even animal scats! They were experiencing this place in a far more holistic way than I was, and it was captivating to watch. The best was yet to come, however, when one lady from our group, Jedda, spotted not one but three lyrebirds! The Taungurung rangers were in disbelief, as this was their first sighting, too. Jedda later told me that she had been sitting quietly, talking to, and listening to Country, and thanking the ancestors for welcoming her and protecting her during her visit. It was then that the lyrebirds appeared. As Aunty Jo had said in her welcome, “When we listen to Country, Country speaks to us in all different ways”.

By the end of our time with the desert rangers, their confidence had grown exponentially. They had learnt so much about themselves, about rangers in other parts of Australia, and about navigating the mainstream world through a big city. Simply by being a part of this program, these women will be equipped to take on more opportunities than they could before. They will also continue to grow in their roles as rangers and, no doubt, become mentors for the next generation of female Indigenous conservation workers. Personally, I feel privileged to be a part of this program and will continue to learn about and appreciate our First Nations peoples and cultures. Until next year, I will remember to pay attention to the trees above my head, the ground beneath my feet, and the silence of nature that speaks through the wind, the birds, and the running waters.

With thanks to Indigenous Desert Alliance, our partner in the Desert Women’s Leadership program.

We would also like to acknowledge and thank the following organisations for making this year’s trip possible:

APT Travel Group and OneTomorrow Fund

Australian Unity and The Australian Unity Foundation